We have been using multiple intelligences in this class. we read,

speak, talk, write, interact. And one of our subtopics has been the

connections between all art and creatibe writing. Continuing that

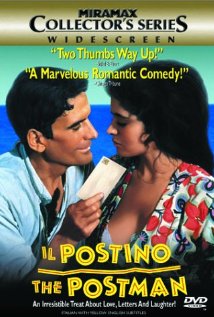

discussion, film critic Jim Dalrymple writes that Il Postino (1994) is the kind of film:

We have been using multiple intelligences in this class. we read,

speak, talk, write, interact. And one of our subtopics has been the

connections between all art and creatibe writing. Continuing that

discussion, film critic Jim Dalrymple writes that Il Postino (1994) is the kind of film:That’s unwaveringly committed to its story, while somehow also managing to be heartwarming and charming. The story depicts a chapter Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s exile, as well as the fictional relationship that he forms with an Italian postman. As the postman delivers mail to Neruda he learns about the power of poetry, first in love and eventually in politics. Neruda’s poetry is affective and simply amazing, and few films that include poetry are as overtly about it as Il Postino. However, and perhaps most importantly, Il Postino ultimately makes the argument that poetry matters as a force for good in the world.

The writing of poetry is a form of literary art which uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language—such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre—to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, the prosaic ostensible meaning.

Poetry has a long history, dating back to the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. Early poems evolved from folk songs such as the Chinese Shijing, or from a need to retell oral epics, as with the Sanskrit Vedas, Zoroastrian Gathas, and the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Ancient attempts to define poetry, such as Aristotle’s Poetics, focused on the uses of speech in rhetoric, drama, song and comedy. Later attempts concentrated on features such as repetition, verse form and rhyme, and emphasized the aesthetics which distinguish poetry from more objectively-informative, prosaic forms of writing. From the mid-20th century, poetry has sometimes been more generally regarded as a fundamental creative act employing language.

Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest differential interpretation to words, or to evoke emotive responses. Devices such as assonance, alliteration, onomatopoeia and rhythm are sometimes used to achieve musical or incantatory effects. The use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations. Similarly, metaphor, simile and metonymy create a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived. Kindred forms of resonance may exist, between individual verses, in their patterns of rhyme or rhythm.

Some poetry types are specific to particular cultures and genres and respond to characteristics of the language in which the poet writes. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz and Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter; there are, however, traditions, such as Biblical poetry, that use other means to create rhythm and euphony. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition, playing with and testing, among other things, the principle of euphony itself, sometimes altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm. In today’s increasingly globalized world, poets often adapt forms, styles and techniques from diverse cultures and languages.

____

Introducing Poetry throughout the School Day

For millennia – even before Homer started reciting The Iliad and The Odyssey – we humans have been telling one another poems. Even today, children and adolescents often spontaneously make up poems to tell one another, in jump-rope rhymes, insults and comebacks, riddles, and other verses. What is it about poems that so appeals to us?

On the other hand, many adults today feel turned off to poetry, never venturing to scribble a verse and rarely listening to it, except when tuning in to a song’s lyrics. What happened to make us so wary of poems?

Why Poems?

Poems intrinsically appeal to us because of their rhythm, their rich imagery, and and their ability to extract the pot-liquor from the boiling cauldron of our experiences. Here’s an example: Fog by Carl Sandburg. Click here for the full text of the poem.

How does Sandburg do that – capturing the essential images and impressions of fog in twenty-one small words? To be honest, we can’t tell you exactly how he does it. Perhaps we have to admit that – like electricity – it seems to happen as if by magic.

The secret to the magic isn’t in the topic he chose. In the many anthologies containing Sandburg’s poems, you may find a wealth of other poems about almost any classroom topic you and your children can think of. For instance, you may find Sandburg’s poem in Jack Prelutsky’s (1983) anthology, The Random House book of Poetry for Children (p. 96), New York: Random House.

Prelutsky’s anthology also includes poems on ferns, wind, George Washington, smells, boa constrictors, Halloween, being rude, basketball, waking up, cockroaches, the taste of purple, feeling frightened, a hog-calling competition, family members, unicorns, toasters, flying, and so on – even poems on the whole universe.

Dalrymple continues:

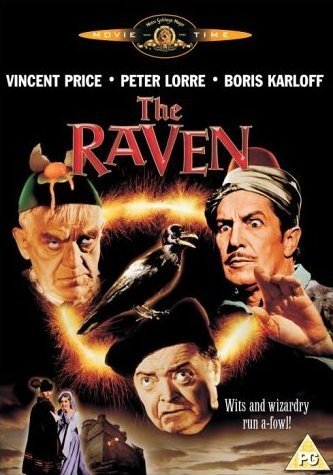

The Raven (1963) — This film is classic Vincent Price: campy, funny in a strangely knowing way, and macabrely delicious. The fact that it also stars the the legendary Boris Karloff is icing on the cake. It’s based, rather loosely, on Edgar Allen Poe’s long poem “The Raven, which you may have read in an English class. Or, you may be familiar with the poem from The Simpsons‘ episode “Treehouse of Horror,” in which it was read by the velvet-voiced James Earl Jones. In any case, Price’s version of “The Raven” provides a good introduction to two cultural essentials: classic poetry, and classic B movies.

No comments:

Post a Comment